When scientists from the Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen and associates in Germany examined birch tar more closely, they discovered a considerably more intricate method for making the glue than was previously thought. They observed that this method was used by Neanderthals

In their paper, “Production method of the Königsaue birch tar documents cumulative culture in Neanderthals,” published in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, the scientists matched several birch tar production processes to the chemical byproducts discovered on prehistoric Neanderthal implements.

The capacity to synthesize materials and substances that are not present in nature is one of the characteristics of human intellect. The use of tools was originally taken into account, but since various animals have been found modifying and manipulating materials to be used as tools, it has lost some of its significance as an indication of intelligence.

According to the reports of Phys, manufacturing synthetic materials still contributes significantly to our cognitive advantage over other creatures since it necessitates conscious thought, planning, and understanding of our behavior in order to transform raw materials using a learnt procedure.

The Tübingen study demonstrates that this skill is not exclusive to contemporary humans and that they were not the first to achieve this mental milestone. Neanderthals utilized birch tar, which is 100,000 years older than any known current human adaption. With the extra bonus of being water-resistant and resistant to biological decomposition, the sticky substance was employed as an adhesive backing to join stone to bone and wood in tools and weapons.

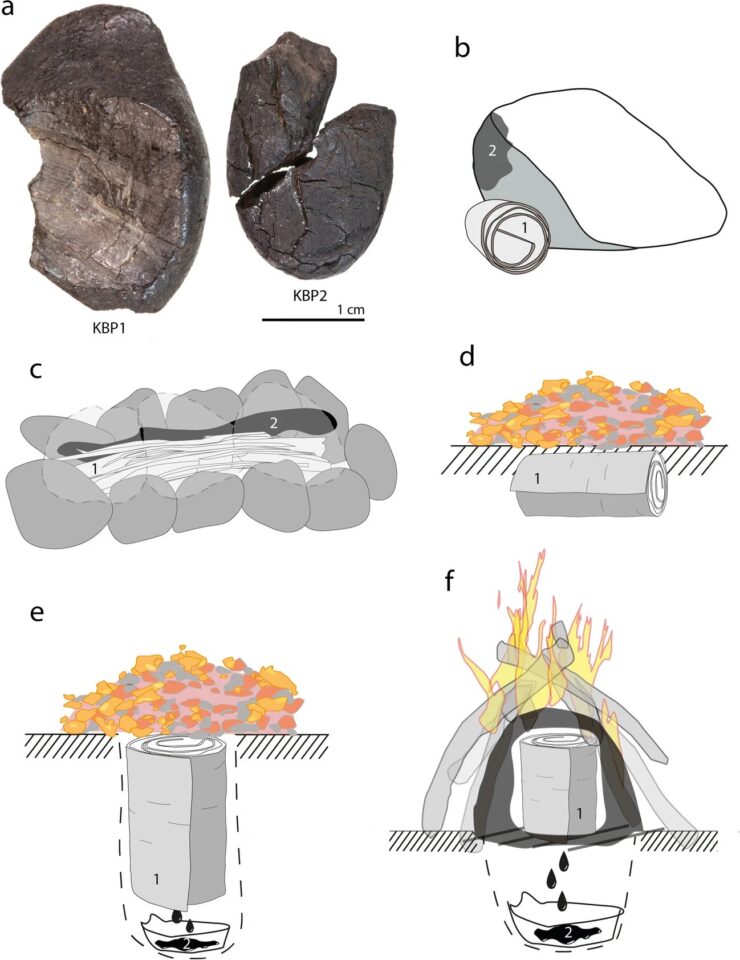

It’s been hypothesized that Neanderthals either created birch tar or obtained it by scraping it off of rocks after a fire. The researchers discovered that Neanderthals did not just locate birch tar after a fire or employ the most straightforward manufacture process. Instead, they used a huge reference collection of Stone Age-made birch tar artifacts and a comparative chemical examination of two German birch tar artifacts.

Instead, scientists now know that the Neanderthals who produced German birch tar employed the most effective technique, a series of subsurface heating and oxygen-restricted distillation steps to extract the synthetic glue.

The authors contend that a level of complexity of this magnitude is unlikely to have arisen accidentally. suggesting that the more complicated procedure would have been evolved via trial from simpler approaches at first.

The researchers used experimental archaeology to recreate five distinct extraction procedures, two above ground and three below earth, to examine the method that produced the German birch tar. The scientists used gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, infrared spectroscopy, and micro-computed tomography to extract the birch tar, analyze it, and compare it to the old birch tar artifacts.

On the experimental tars, oxygen availability at the moment of extraction left a distinct imprint, producing a signature that distinguished above-ground from below-ground techniques. The underground production method matched the antiquity of the objects. In contrast to above-ground methods, both ancient tar artifacts and the studies conducted underground demonstrated some soil mineral interaction and were devoid of soot-related carbons.

Because some parts cannot be seen or changed after the operation starts, underground transformational procedures are more difficult to carry out than above-ground approaches. This necessitates a more exact setup procedure.

The proof that Neanderthals were intellectually sophisticated has only grown in recent years, since archaeological data shows that many of the innovations that were formerly assumed to be exclusive to modern humans were actually used by Neanderthals. Anyone who chooses to view human intellect as an uncommon uniqueness may find it advantageous at this point to acknowledge that Neanderthals were also humans.

According to the authors, “… Neanderthal birch tar making seems to be the first documented manifestation of this kind in human evolution.”