Based on a re-analysis of a cave lion skeleton and recently discovered claws, research has revealed that Neanderthals may have hunted cave lions.

According to a new paper published in the journal Scientific Reports, Neanderthal hunters living in present-day Germany 48,000 years ago killed a large cave lion. This action may be the earliest known example of lion hunting. Gabriele Russo of the University of Tubingen and co-authors base their conclusions on close forensic analysis of a cave lion skeleton that shows evidence of having been wounded with a wooden spear. They also analyzed the paw bones of a recently discovered cave lion, which show evidence of having been skinned about 190,000 years ago.

Larger than modern mountain lions, cave lions were apex predators and are now extinct. According to the authors, they were frequently depicted in Paleolithic art, and their body parts were utilized as ornaments—part of a long-standing interaction between hominids and carnivores that influenced cultural habits. Although it is known that hominins have interacted with lions since the animals first arrived in Europe, less is known about earlier interactions between carnivores and hominims such as Neanderthals.

Although Neanderthals were skilled hunters who were known to dispatch bears and other animals, there is little proof that they ever interacted with cave lions. While other lion bones from the same period recovered in Southwestern France have cut marks indicative of skinning, a pair of Middle Paleolithic lion fibula unearthed in eastern Iberia had cut markings indicating the lion was killed. The most recent study a reassessment of a male, medium-sized cave lion skeleton that was discovered in Siegsdorf, Central Germany, in the 1980s.

Cut marks on a number of the bones (two ribs, the left femur, and a few vertebrae). These traces indicate that the animal was butchered after it had died, indicating scavenging rather than active hunting. However, based on comparable scars observed on deer vertebrae, Russo et al. also discovered evidence of hunting lesions, most notably a partial puncture wound on the interior of the third rib typical of the impact from a wooden-tipped spear. The puncture is too deep and does not have the characteristic pits and perforations of teeth from another carnivorous species.

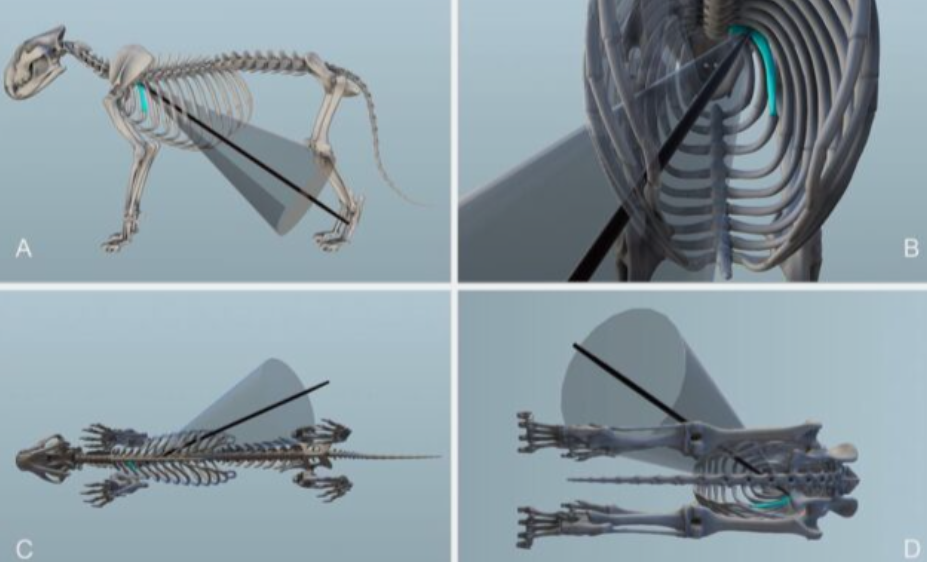

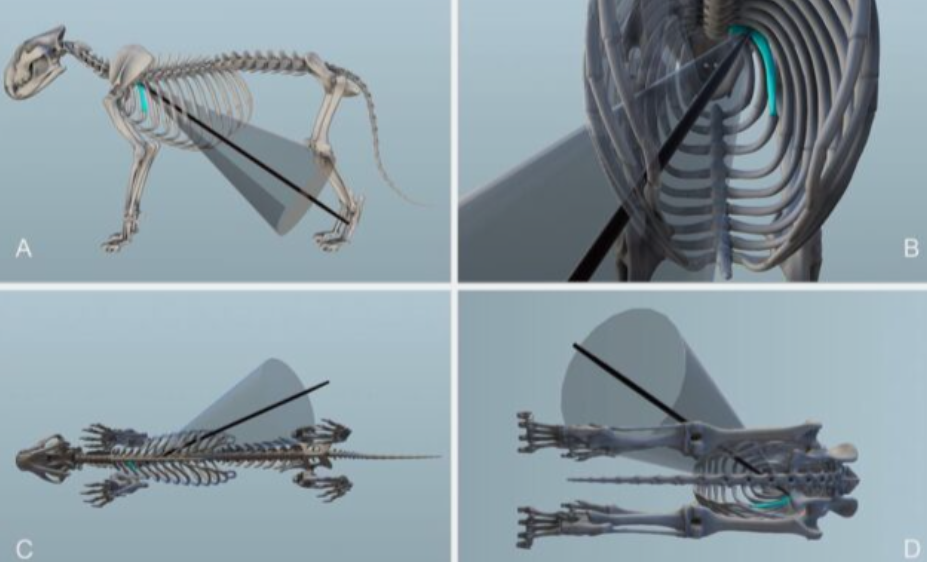

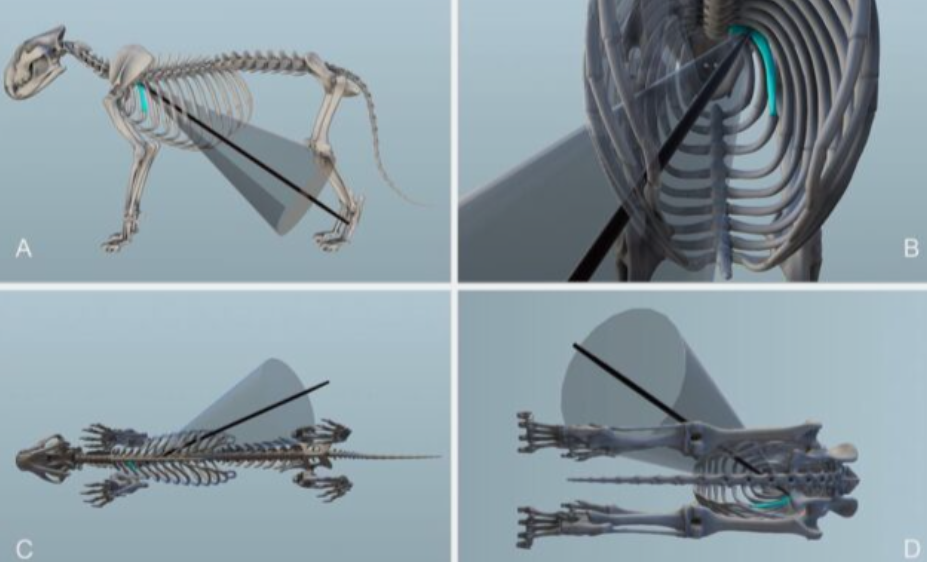

Reconstructing the impact angle, penetration depth, and direction of a wooden-tipped spear on the ribcage allowed the scientists to test their theory. Based on such details, it appears that the spear entered the cave lion’s abdomen from the left side and traveled through important organs before striking the right side of the ribcage. The authors came to the conclusion that the animal would have died from this wound. While throwing and thrusting weapons were frequently employed side by side, they also discovered some evidence of drag marks, so “it remains possible that [the] drag marks may indicate that spears were thrown at the lion,” they stated.

Based on the sediment layer in which they were located, the researchers also examined cave lion claw bones that they recovered in the Einhornhöhle Cave in Germany in 2019. These bones are thought to be at least 190,000 years old. Those bones showed cut marks consistent with skinning, with care taken to preserve the claws within the fur. The authors speculate that this may be the first instance of Neanderthals using a cave lion’s pelt for cultural reasons in Central Europe.

Russo et al. wrote that the lion claws “set them apart from examples found in the archaeological and ethnographic record, suggesting their unlikely use as such, as they lack polish, wear, perforations, or any distinctive features associated with pendants or clothing components.” This suggests that the carcass was probably skinned elsewhere from a fresh kill, and that only the pelt—possibly just the paws—was brought back to the cave. “We conclude that Neanderthals were capable of engaging with non-human predators such as lions not only economically but also culturally—as Homo sapiens also is evidenced to have done later in time.”

Cover Photo: Depiction of Neanderthals after taking down a lion. Julio Lacerda