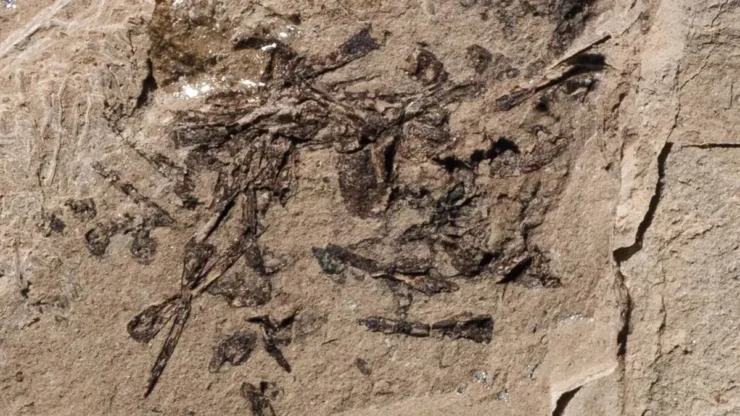

Palaeontologists discovered a fossilised pile of small bones in Utah’s Morrison Formation. At first, the Utah Geological Survey team questioned if they had uncovered a strange new species. When they looked closely, they discovered that the bones belonged to a range of amphibians that were swallowed by a larger predator 150 million years ago, who then threw them up.

John Foster said, co-author of a report on the discoveries, ‘This fossil gives us a rare glimpse into the interactions of the animals in ancient ecosystems.’

The prehistoric vomit was discovered in the Morrison Formation, a well-known Late Jurassic site noted for its dinosaur bones. Fossils from the late Jurassic era are abundant in this section of sedimentary strata that spans the Western United States (164 million to 145 million years ago). The formation, is frequently home to dinosaur fossils like those of Camarasaurus, Diplodocus, Apatosaurus, Stegosaurus, and Allosaurus. Local paleontologists refer to this area in particular as the “Jurassic salad bar” because it frequently includes fossilized plant and other organic material in addition to animal bones.

The researchers was initially unaware that they had discovered ancient vomit. Instead, the scientists thought they had uncovered the bones of a single animal. “Looking closer, most of the material is from a frog and at least one salamander. It was then that we started suspecting that what we were seeing was puked out by a predator.” Foster said.

According to the news of Science alert, among those remains are vertebrae from one or more undetermined species and amphibian bones, notably femurs from a frog and a salamander. And some bones were only 0.12 inches long.

The fossil’s chemical analysis confirmed that it is a fossilized form of vomit known as ‘regurgitalite.’ Although there have been a number of recorded findings of regurgitalites around the world, Foster said that this is the first known instance of one at the Morrison Formation, calling the discovery “one of a kind”.

While it is impossible to know which type of animal lost its lunch millions of years ago, or why it upchucked in the first place, future investigation could reveal other components of the partially digested animals that the predator devoured.

“We think that there’s more to this thing than just the tiny bones of amphibians,” Foster said. In order to locate more prehistoric fossils, the researchers plan to continue exploring the area.

Co-author of the research James Kirkland said: ‘We must now carefully dissect the site in search of more tiny wonders in among the foliage.”