The long necks of giraffes have been presented as a prime illustration of natural selection for years. A freshly discovered fossil girraffoid, on the other hand, suggests a new hypothesis. A long-extinct species appears to have evolved a battle-ready head and neck, and giraffes appear to have followed in their footsteps.

According to popular belief, ancestral giraffes with longer necks than their peers were able to reach more nutritious leaves at the tops of trees, making them more likely to survive and reproduce. Their descendants inherited this trait, resulting in ever-lengthening necks.

However, survival of the fittest is not the only evolutionary driver. Darwin was aware that sexual selection plays a role, and since his time, additional complications have been recognized. Some zoologists believe that the struggle for mates may have contributed to giraffes’ massive necks, and new evidence published in the journal science supports this theory.

Male giraffes compete for dominance and mating opportunities by swinging their heads at each other. They may not understand the physics of torque, but as a species, they’ve figured out that longer necks equal more head hitting power. Males also employ the force of a well-swung skull to push ladies to urinate in order to determine their fertility. It’s very lovely!

So, did the necks evolve to reach treetops or to whack opponents? In the normal course of events, distinguishing causes can be difficult, especially for a trait that evolved millions of years ago. Professor Deng Tao of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and his colleagues, on the other hand, struck gold with a 16.9 million-year-old fossil discovered in the Junggar Basin of Xinjiang. They named the newly described species Discokeryx xiezhi – Discokeryx is one of the oldest members of the giraffoids superfamily, which is now limited to two species of giraffe.

“Discokeryx xiezhi featured many unique characteristics among mammals, including the development of a disc-like large ossicone [horn-like structure] in the middle of its head,” said Deng in a statement.

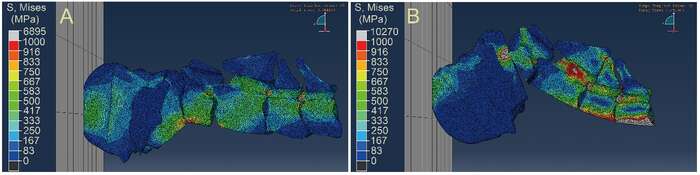

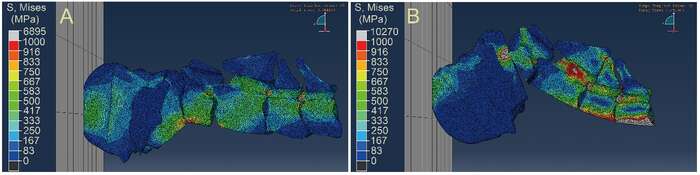

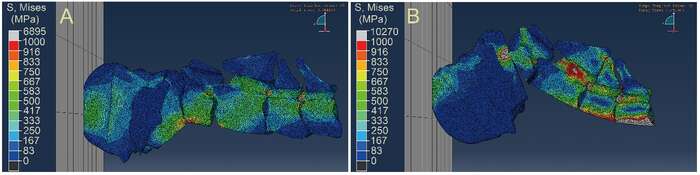

Its ossicone was perfectly honed by evolution to be effective in head-to-head battering contests. Indeed, the authors conclude it was better at its job than equivalent structures in the skulls of modern animals such as musk-oxen that compete for dominance in similar ways. Discokeryx‘s neck vertebrae were thickened to provide support in such battles, while the head-neck joints are the most complicated ever seen in mammals, presumably for the same reason.

The authors conclude that giraffes have been employing head-butting to win mates for a long time, long before they developed such massive necks. “Fossil giraffoids have a larger degree of variability in headgear morphology than any other pecoran group,” they add, “and this diversity, together with the complicated head-neck morphology, certainly suggests the intense sexual combats between males in the evolution of giraffoids.”

The use of the head and neck as a weapon was ingrained in the ancestors of modern giraffes five million years ago. Males would have benefited from longer necks in order to exert more force. Access to leaves beyond the reach of other animals was probably secondary, though the teeth of the much shorter-necked Discokeryx indicate it also fed on tree leaves.

Despite the fact that Discokeryx lived in a warmer and wetter world than today, the Junggar Basin was drying out due to Tibet’s rise, creating an ecosystem similar to today’s East African Savannah.

The name xiezhi was chosen because of its resemblance to the mythical Chinese animal of the same name, while the genus name Disco (round plate) and keryx were combined (meaning horn). Unfortunately, there is no evidence that Discokeryx liked to boogie; it appears that the males were fighters rather than dancers.