A new Rice University-led study of ancient predators remains reveals new information about how prehistoric humans found – or did not find – food.

For more than three decades, archaeologists thought that one potential source of meat — crucial for the development of the early human brain — was the flesh abandoned from sabertooth cat kills. Until very recently, researchers thought that prehistoric humans stripped flesh from abandoned animal carcasses to consume, but these ancient remains suggest that was not the case. The new research, conducted on fossil remains from 1.5 million years ago, reveals that sabertooth cats fully devoured the flesh of their prey and even consumed some bones.

These iconic ancient predators, named for their enormous upper canines, roamed the landscapes of Africa, Eurasia and the Americas from the Miocene to the late Pleistocene. Manuel Dominguez-Rodrigo, a visiting professor of anthropology at Rice and the study’s first author, was able to determine together with his colleagues the eating habits of these prehistoric cats based on their skeletons and those of their prey.

The discovery is significant, according to Dominguez-Rodrigo, because it indicates that early humans relied on various methods to find protein sources. It lends credence to the notion that early humans were already skilled hunters.

Dominguez-Rodrigo said the research helps further this area of study as it eliminates a source of this important type of food for ancient humans. However, he said, there are still a lot of unanswered questions about how prehistoric humans hunted and gathered food, and these topics will be the focus of future work.

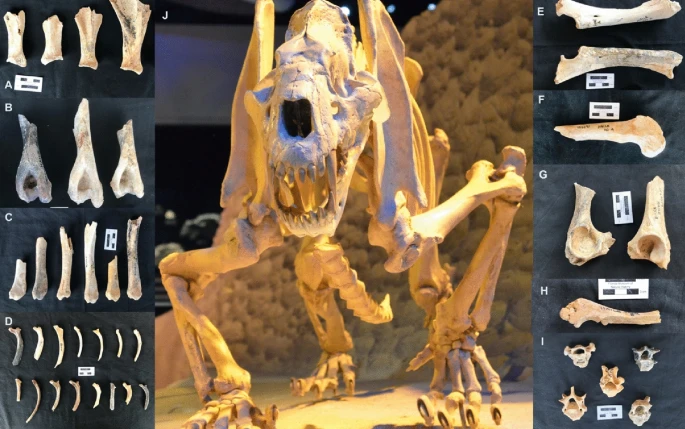

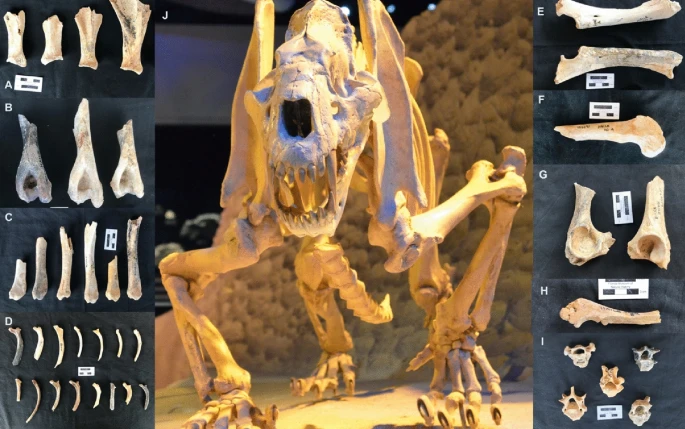

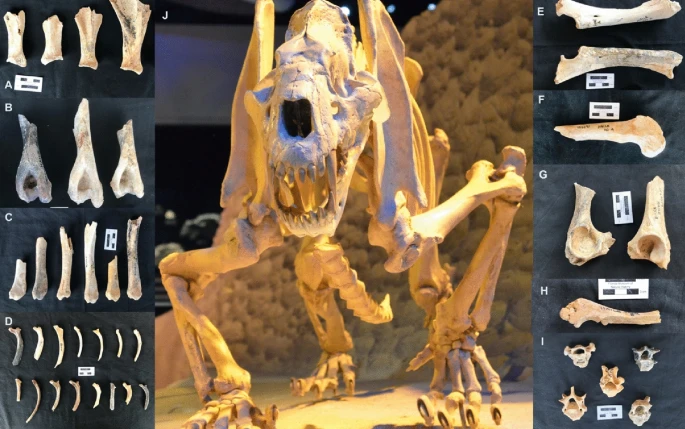

Cover Photo: Examples of African warthog carcasses consumed by modern lions.

Source: Rice University