Many of our questions about how they lived and what they were like would be answered if we lived in a world where happy tourists could travel to a remote island resort and see living dinosaurs or run for their lives from them, as in Jurassic World Dominion (2022). Unfortunately, we must rely on information gleaned from fossil remains preserved in rock tens of millions of years ago. In addition, new discoveries such as the belly button found enlighten us.

About dinosaurs there is still so much we don’t know. The process of decay and mineralization that occurs during fossilization removes surface features from dinosaur remains, leaving us to infer their appearance and behavior from the bones they leave behind. However, an exceptionally well-preserved animal may retain some surface features, providing us with a rare glimpse into their anatomy.

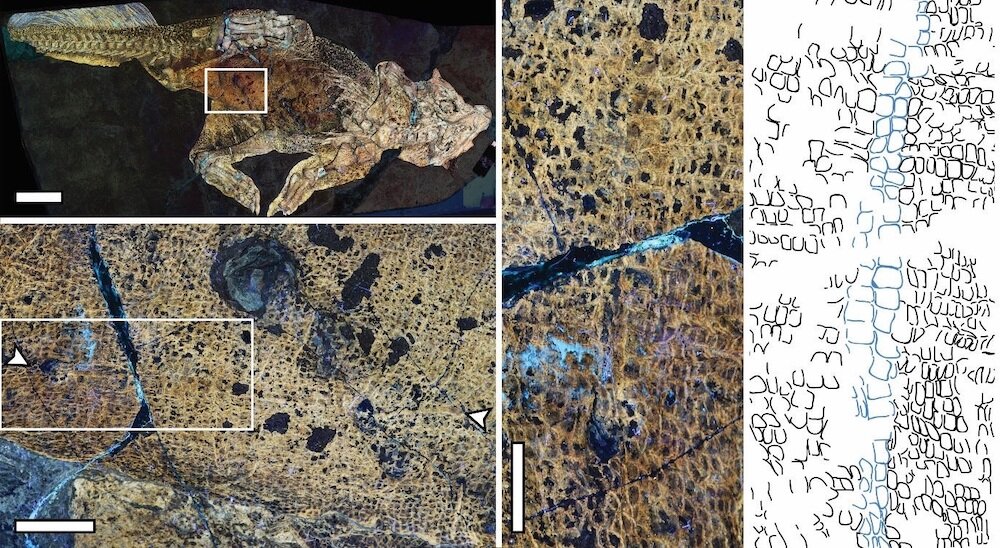

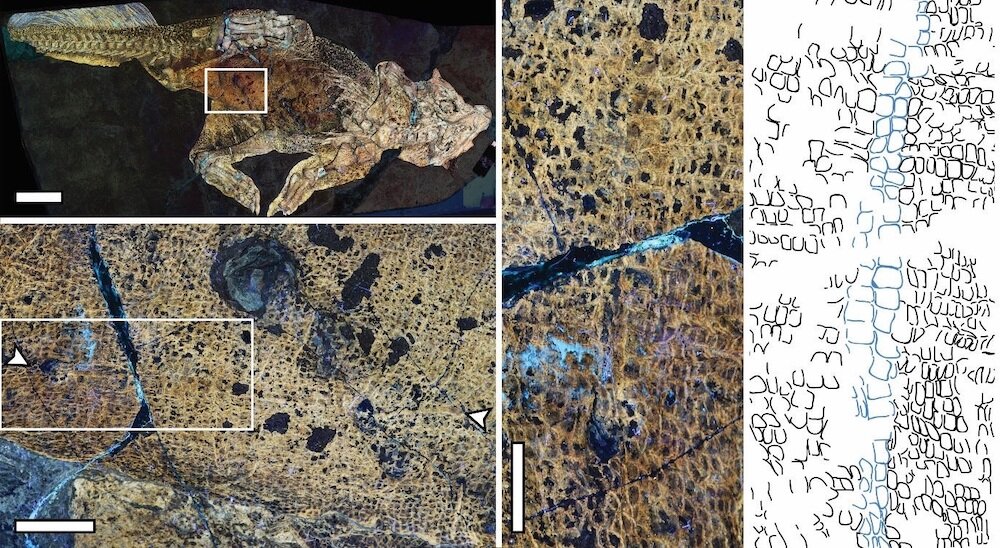

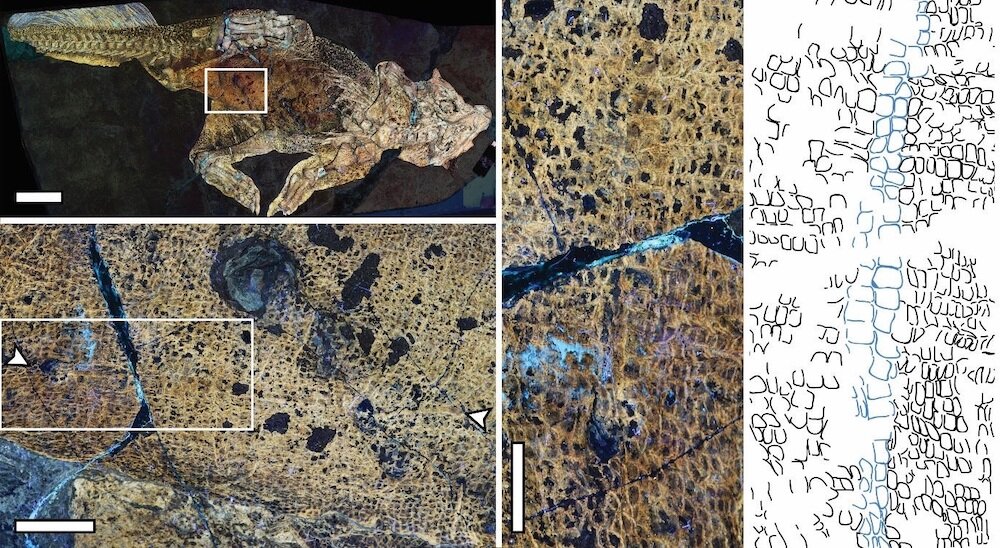

Michael Pittman of the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s School of Life Sciences and colleagues studied an unusually well-preserved Psittacosaurus. Previous research on the animal revealed some amazing features such as a row of thin porcupine-like quills along its tail and a preserved cloaca. New imaging techniques have now revealed a previously unseen feature in dinosaurs: a 130-million-year-old belly button. The research was published in the journal BMC Biology.

“With our laser fluorescence technique, my co-author, Thomas G. Kaye, and I imaged it, and it showed all of this new information in the material that we couldn’t see before,” Pittman told SYFY WIRE.

Laser-stimulated fluorescence imaging is the official name of the technique, which depends on interactions between laser light and minerals in the fossil to expose buried data. A long-exposure photograph is created by scanning a line of laser light across a specimen in a dark room. When laser light collides with a fossil, it interacts with minerals and emits a variety of hues, depending on the substances it comes into contact with. This provides scientists with a chemical map of a specimen, revealing nuances in the preservation that aren’t evident to the naked eye.

Despite 20 years of research, scientists were able to reveal previously unseen characteristics in the skin of their Psittacosaurus specimen using this technique. A row of specialized scales depicting an umbilical scar, also known as a belly button, was among the novel discoveries.

“Typically, you think of umbilical cords as being a mammal thing. If you look inside the embryo of a bird, which are the only living dinosaurs, or the embryo of a croc which is a close living relative, you’ll find the embryo connects to the yolk sack which provides nourishment and to the allantois which gets rid of waste products,” Pittman said.

That connection resembles the umbilical cord we’re familiar with in placental mammals in terms of appearance and function, but there are several key distinctions. The umbilicus of a bird, reptile, or dinosaur isn’t as well-defined as an umbilical cord, which is a discrete cable traveling from the embryo to the placenta. The embryo is connected to the connection along a slit on the abdomen, rather than at a single spot. Then, rather of being cut after birth, like in mammals, it severs on its own when the animal is ready to hatch, and the slit closes.

“In some modern species, it heals over perfectly very quickly after birth. In some species, they keep it throughout their lives. Some keep it halfway before it fades away. In the case of our Psittacosaurus, it was just shy of sexual maturity. It’s persisting quite late in its life,” Pittman said.

The tremendous degree of variety in umbilical scars found in current birds and reptiles shows that dinosaurs had a similar degree of variation. This suggests that some dinosaurs had umbilical scars well into maturity, whereas others had them healed early on. According to Pittman, this variance exists not just between species, but also between individuals.

“We only have one data point but I’m expecting to find more of them, but we need to be in a position where we have specimens of the right quality to find them. We have to be able to look at specimens that preserve the skin, but there aren’t that many of those,” Pittman said.

Some mummified hadrosaur fossils that Pittman thinks might be good candidates for more belly buttons are of particular interest in the hunt for more belly buttons. Using new imaging techniques on existing fossil collections could reveal previously unseen features in animals that are and have been right under our noses.

While the current population of dinosaurs with belly button is small, it’s likely that most dinosaurs had them, and with this knowledge we can feel them in reality. As different as we are, we share a small imperfections in our bodies which leave a lasting reminder of the unbroken chain of life stretching from today, all the way back to the Cretaceous and beyond.