The Victoria & Albert Museum has sent a life-sized marble head of Eros back to Turkey. The 3rd century Sidamara Sarcophagus is one of the biggest, heaviest, and most significant Roman sarcophagi ever discovered. V&A conservators traveled with the head and collaborated with specialists from the Istanbul Archaeological Museum to reattach it to the lid.

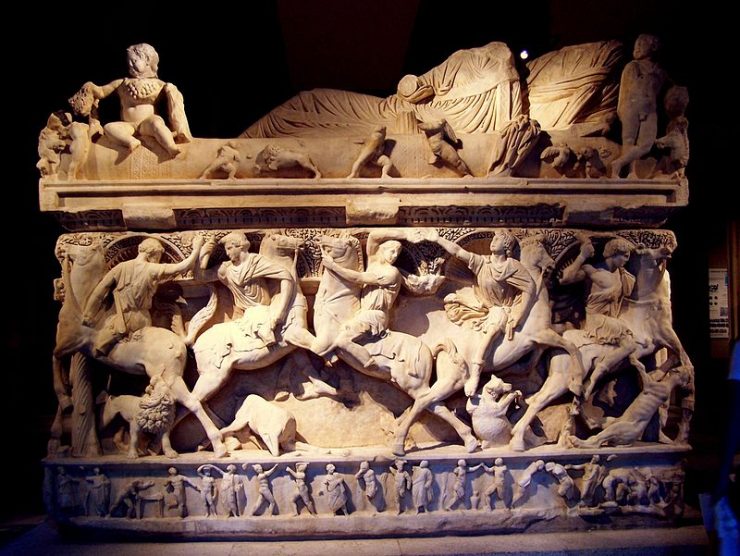

The Sidamara Sarcophagus is a unique find because of its size and design. It was created in Anatolia on the basis of earlier Hellenistic counterparts. The sarcophagus is 12.5 feet long and 6 feet 4 inches wide, about twice as long as it is wide, like other significant sarcophagi carved in the Athenian manner. It is deep relief and finely carved. The sarcophagus’s owner and his wife are depicted as lying down on the lid as a man and lady. On the top corners of the front are two eroses. The Eros in the left front corner has a new head.

The men hunting for wild animals in a forest are depicted on the façade’s front. The ends of the landscape are capped by two trees with twisted trunks and large canopies. The opposite long side features a man in philosopher’s robes sitting in the middle and clutching a scroll. A woman with her head covered is standing to his left; she may be his wife. The goddess Artemis is positioned to his right. The tableau is framed by the horses of the Dioscuri, also known as the divine twins Castor and Pollux. An architectural backdrop with ornately detailed columns, capitals, and pediments is visible behind them.

On one of the short sides, a woman holding a fruit offering is shown standing in front of a tomb’s door. A hunting scene is engraved on the other short side. The sarcophagus’ base and lid are decorated with friezes that show cupids engaging in animal combat, athletic competitions, and chariot racing.

Near 1882, the enormous sarcophagus was found in the ancient city of Sidamara (current-day Ambar), in south-central Turkey. Major General Sir Charles Wilson, then-military Britain’s consul general in Anatolia, made the discovery. In order to keep the discovery under wraps until his return and arrangements to have the sarcophagus moved to Britain, he immediately reburied it. Meanwhile, he severed the head of Eros and brought it back to England, where he loaned it to the South Kensington Museum in 1883. (now the V&A).

He had difficulties in his attempt to safeguard the tomb and return it to the Head of Eros in England. A year before Wilson discovered the sarcophagus, in 1881, Osman Hamdi Bey, an Ottoman official, artist, and pioneering archaeologist, had been appointed director of what was then the Imperial Museum. He was a powerful proponent for stricter rules that forbade the export of archaeological items. Although there were previously rules in place, their implementation was lax, making it simple for diplomats, military personnel, and other representatives of European countries to sneak artifacts out of the country with impunity. Breaking that loop was made possible in large part by Osman Hamdi Bey.

The sarcophagus was rediscovered by a local villager in 1898. He reported it to Imperial Museum and Osman Hamdi Bey arranged for its removal to Istanbul. It took teams of water buffaloes to budge the gigantic piece from the find site, and then a special train to take it to Istanbul. It was installed in the museum in 1901.

After Wilson’s death his daughter donated the head to the V&A in 1933. According to the V&A, a visitor to the museum in 1933 noticed that the head looked like a good match for the Sidamara Sarcophagus and V&A staff sent a plaster cast of the head to confirm whether it was a perfect fit. It was. At this crossroads, the V&A seemed prepared to return the head in a gross but typical quid pro quo. They’d return the head if Turkey gave them a Byzantine marble of equal value.

The deal was simply never pursued, despite having official approval. The minutes of V&A director Eric Maclagan from April 1934 might shed light on why they would want to just sort of ghost Turkey on the question. The return of this one little head, Maclagan feared, would “raise the difficulty of possible repercussions, particularly with regard to the Elgin Marbles, but I think we could justify ourselves by pointing out that this is a question of a single head missing from a large monument, of much more value if replaced than if exhibited by itself.”

The plaster cast was mounted to the sarcophagus and stood in for the real thing for 88 years while the real head remained deracinated and alone in London. Molasses-slow negotiations resumed in 2010. Now, another dozen years later, the V&A has finally signed a partnership agreement with the Turkish Ministry of Culture & Tourism and the Istanbul Archaeology Museum, sealed with the return of the head.

Before a team from the V&A flew to Istanbul with the Head of Eros in June 2022, a team from the V&A underwent an initial conservation treatment at the V&A in London, where the marble head was cleaned and an old metal dowel was removed. This generous support was provided by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Turkish Airlines. In Istanbul, the teams worked to remove the old dowel and replace it with a new, adjustable stainless steel dowel before reattaching the marble head to the sarcophagus.

The Sidamara sarcophagus, which has now been completed after more than a century, is on display at the Istanbul Archaeological Museum.