A new analysis of a 5000 year old mass grave in Spain, where traces of a sophisticated Neolithic battle have been found, reveals that the site was a burial place for fallen warriors.

Men, women, and children who had suffered arrow wounds to the head and were buried in a mass burial in Spain more than 5,000 years ago. According to a recent study, archaeologists have now unraveled this complex network of remains to uncover fresh proof of historical warfare.

The San Juan ante Portam Latinam (SJAPL) rock shelter was first excavated in 1991. It is located in the town of Laguardia in northern Spain. More than 300 skeletons dating between 3380 and 3000 BC were found in this mass grave, many of them intertwined and in strange positions. Dozens of flint arrowheads, knives, stone axes and personal ornaments were also discovered.

Researchers initially thought they had found evidence of a Neolithic massacre. But a new analysis of the skeletons revealed that these people were most likely killed in separate raids or battles lasting several months or years.

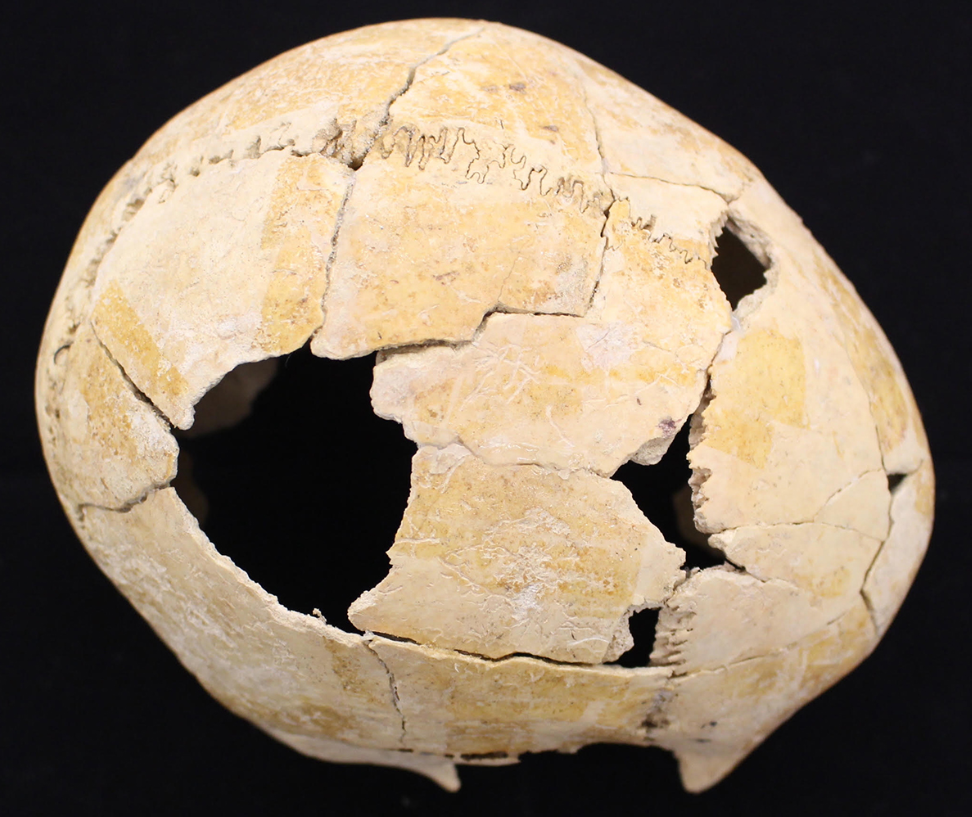

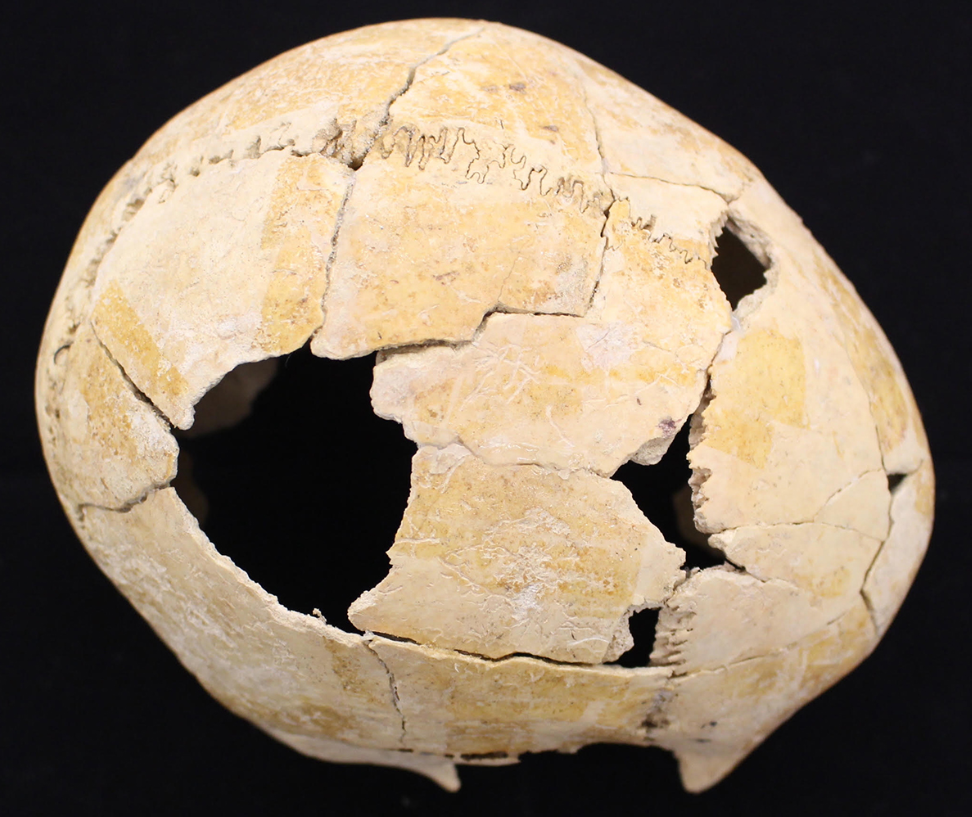

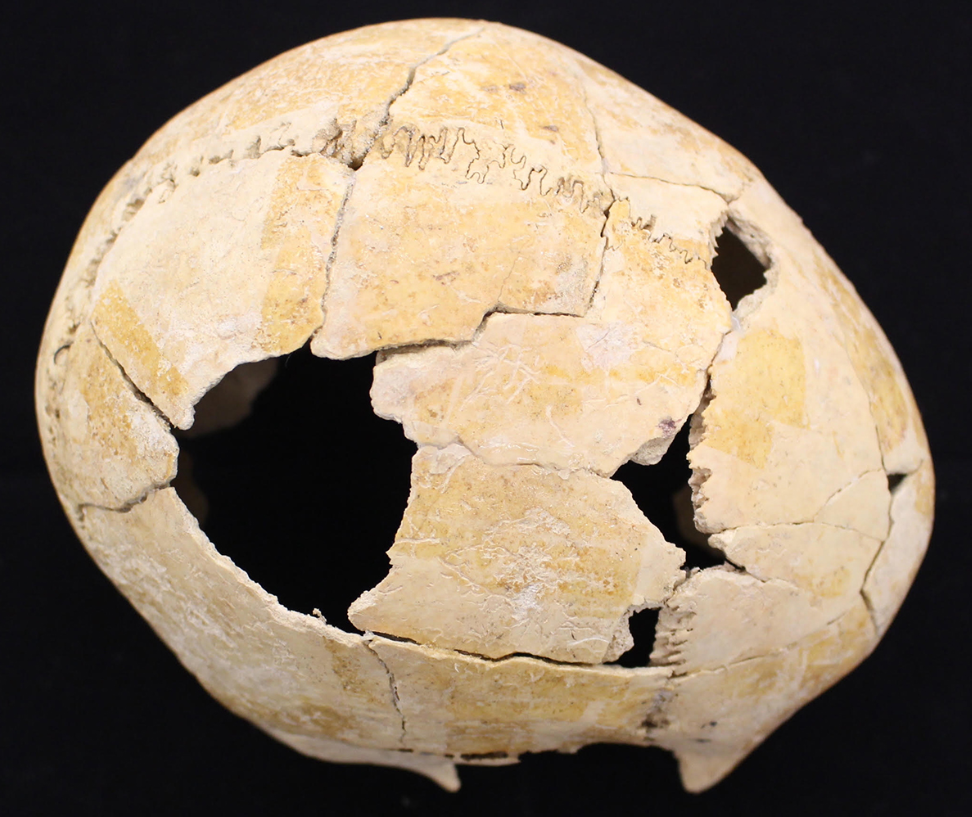

First author Teresa Fernández-Crespo, an archaeologist at the University of Valladolid in Spain, and her team describe healed and unhealed injuries on SJAPL skeletons. They found a total of 107 cranial injuries, most of them located in the upper part of the skull and probably corresponding to trauma such as blows from stone maces or wooden sticks. The researchers found that men suffered almost five times more skull trauma than women.

Injuries to the rest of the skeletons were also analyzed. The team found 22 cases of trauma affecting limbs, mostly spiral or V-shaped fractures, and 25 injuries to other parts of the body. As with skull injuries, these seem to have affected men the most. Arrowhead injuries are also strongly linked to male skeletons, suggesting that men are more often exposed to violence than women.

As a result, gender identifiable adolescent and adult males buried at SJAPL account for 97.6% of the unhealed trauma and 81.7% of the healed trauma recorded. According to the study authors, this mass grave represents male-dominated wars and one or more layers of warfare resulting from the raids.

“We think we are seeing the result of a regional inter-group conflict. Resource competition and social complexity could have been a source of tension, potentially escalating into lethal violence between communities” said Fernández-Crespo.

Late Neolithic communities of several hundred people each were mostly farmers, growing wheat and barley and tending herds of domesticated sheep, cattle and pigs. But additional evidence of disease and stress that the team found in Neolithic skeletons suggests that food shortages may have affected people.

“This research makes a convincing case for inter-regional conflicts where male combatants die in battle. The fact that 338 individuals had more non-fatal injuries than fatal injuries suggests that many people recovered from their wounds, which may indicate that regional conflicts were not epic battles,” said Ryan Harrod, a bioarchaeologist at the University of Alaska Anchorage.