Archaeologists from the University of Leicester discovered a 4000 year old gold working tool kit among the grave items from a significant Bronze Age burial close to Stonehenge.

The tool kit, which was initially discovered more than two centuries ago, is composed of an alloy of copper and stone, but its purpose has remained a mystery up to this point.

Now, a team of researchers from the University of Leicester have re-examined the grave goods found with the burial, revealing they are good working tools.

The tools were first found at the Upton Lovell G2a Bronze Age burial, which was excavated in 1801 and are now on display at the Wiltshire Museum in Devizes.

Dr Christina Tsoraki, from the University of Leicester, carried out wear-analysis of the grave goods at the museum in Devizes as part of the Leverhulme-funded “Beyond the Three Age System” project.

In the process, she noticed what appeared to be gold residues on their surfaces. It also became clear that the stone tools had been used for a range of different purposes – some were used like hammers and anvils whereas others had been used to smooth other materials.

Dr Tsoraki’s findings prompted the team to work with Dr Chris Standish, from the University of Southampton, an expert in Early Bronze Age gold working.

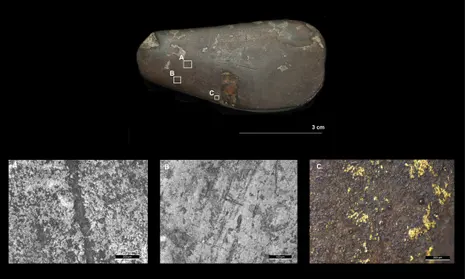

Together Tsoraki and Standish looked at the residues using a Scanning Electron Microscope coupled to an Energy Dispersive Spectrometer to both confirm this identification, and investigate whether the residues were ancient or modern.

The team’s research, published in the journal Antiquity, confirmed that gold residues are present on five artefacts.

They also found that these residues are characterised by an elemental signature consistent with that of Bronze Age goldwork found throughout the UK.

The Upton Lovell G2a burial already held a special place in archaeological narratives. It’s located near Stonehenge and marked with an earthen mound.

Two individuals were buried at the site in association with a wide range of grave goods, including a large number of perforated bone points that are thought to have formed part of an elaborate costume.

These objects were part of the landmark ‘World of Stonehenge’ exhibition at the British Museum but are now back on display in Wiltshire.

Research by Dr Colin Shell in the 2000s identified possible gold traces on one of the stone grave goods.

This new research has identified a further four stone objects with gold on their surfaces and characteristic wear traces, linking a wider suite of items from the burial to the gold working process.

It also demonstrates that these gold traces are ancient. The team suggests the tools were used to make multi-material objects where a core object was crafted in a material like jet, shale, amber, wood or copper and decorated with a thin layer of gold sheet.

Lead author Dr Rachel Crellin, from the University of Leicester, said “This is a really exciting finding for our project.

“At the recent ‘World of Stonehenge’ exhibition at the British Museum, we know that the public was blown away by the amazing 4000-year-old goldwork on display.

“What our work has revealed is the humble stone toolkit that was used to make gold objects thousands of years ago.”

The leader of the Beyond the Three Age System project, Dr Oliver Harris, also from the University of Leicester, said “Our research shows how much more we can find out about how past objects were made and used when we look at them with cutting-edge modern equipment.

“This helps us understand the highly skilled processes involved in making gold objects in the Bronze Age, and shows the continuing importance of museum collections.”

Lisa Brown, the curator at the Wiltshire Museum said “We were delighted to be a part of the Beyond the Three Age System project. The man buried at Upton Lovell, close to Stonehenge, was a highly skilled craftsman, who specialised in making gold objects.

“His ceremonial cloak decorated with pierced animal bones, also hints that he was a spiritual leader, and one of the few people in the early Bronze Age who understood the magic of metalworking. New research like this, is invaluable in helping the museum to tell Wiltshire’s ever-evolving story.”