A hill tomb with Sun Altar lost for nearly 180 years has been discovered in County Kerry on Ireland‘s Atlantic coast.

Folklorist Billy Mag Fhloinn uncovered the tomb’s location on a hill overlooking the village of Baile an Fheirtéaraigh (Ballyferriter) on the Dingle Peninsula in the southwest of the country. The peninsula, which juts out into the Atlantic Ocean, is home to numerous prehistoric remains.

The existence of a tomb near Baile an Fheirtéaraigh was recorded in 19th century ancient literature. However, archaeologist Caimin O’Brien of Ireland’s National Monuments Service told Newsweek that its exact location has been lost to history since the last known record of the tomb was made in 1838.

Known locally as Altóir na Gréine (“altar of the sun”), the tomb is thought to have disappeared between 1838 and 1852 when its stones disappeared. It is likely that the stones were crushed and taken away to be used as building material.

Brien said a local antiquarian who visited the site in 1852 recorded that no remains of the tomb remained, a type of megalith, a class of prehistoric monuments built using large stones.

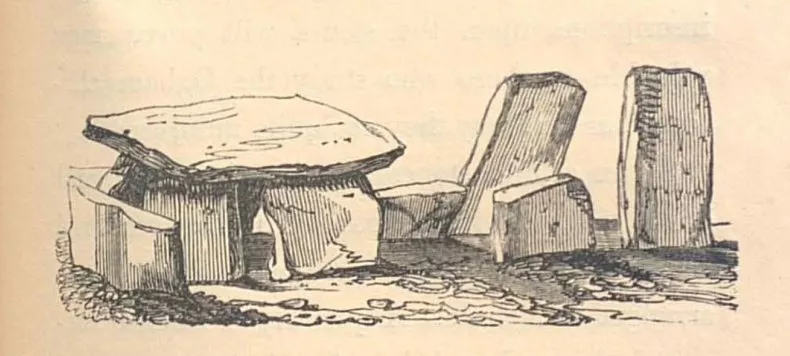

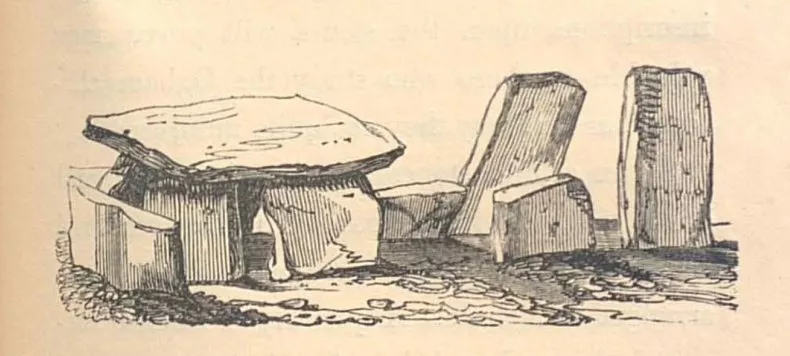

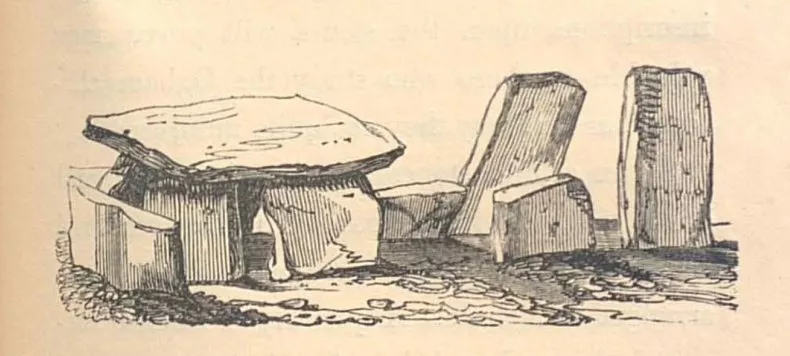

Mag Fhloinn was impressed by the last record of the tomb from 1838, a sketch drawn by Lady Chatterton, an English aristocrat, traveler and writer who visited the area that year. Chatterton published this sketch, showing the monument as it was, in her 1839 guidebook to the region, “Rambles In The South Of Ireland During The Year 1838”.

In addition to the sketch, he wrote the following description of the tomb: “On the top of the hill were the remains of a very curious piece of antiquity, an altar, which it is supposed was once used for offering sacrifices to the sun.”

While exploring the hill known as Cruach Mhárthain in search of the lost tomb, Mag Phloinn noticed a series of orthostats (large upright stones) and a large capstone that turned out to be part of the monument’s structure. This was surprising as it was assumed that the entire tomb had been destroyed.

“I knew there was a lost site of Altóir na Gréine somewhere on the hill, so I started walking up the hill, covering a large area, looking for it. Eventually these stones caught my eye. When I took a closer look, I saw that the features on one of the stones matched perfectly with an orthostat on the 1838 sketch,” Mag Fhloinn said.

He notified the National Monuments Service and O’Brien came to inspect the site. Archaeologists later confirmed that the remains represented the lost Altóir na Gréine tomb. The tomb will be added to the National Monuments database.

According to O’Brien, the monument is a prehistoric type of “wedge tomb“, of which there are several previously found on the Dingle Peninsula and in the wider region. These tombs consist of a long burial gallery, sometimes with a front chamber or a small enclosed chamber. The front part, which is usually wider and higher, always faces west.

O’Brien said evidence from the few examples excavated to date suggests they were built between 2500 and 2000 BC and represent the final phase of megalithic tomb construction in Ireland.

No excavation work has been carried out at Altóir na Gréine. But human remains, both cremated and un-cremated, have been found in other wedge tombs in Ireland.

“These graves are usually positioned on high ground, but not at the highest point. There are certain alignments usually associated with them. Often the opening tends to face west, south or southwest.”

“They often contain cremated human remains and probably represent the burial place of an important family or community group. But they may also have been used for other things, such as ceremonies and rituals. If they face the setting sun to the west and southwest, they could have cosmological and astronomical significance.”

The discovery of the hill tomb with sun altar means that archaeologists can now study it and compare it with others, which could provide more comprehensive information about the prehistoric peoples of this region who built such monuments.