In 2016, when paleontologist Dean Lomax combed through a fossil collection at Yale University’s Peabody Museum of Natural History, he saw a object. It looked like a crocodile that had been squished onto a slate slab. Flaking paint and bits of white plaster revealed that the “skeleton” was a meticulously built plaster cast – and that it did not belong to a crocodile.

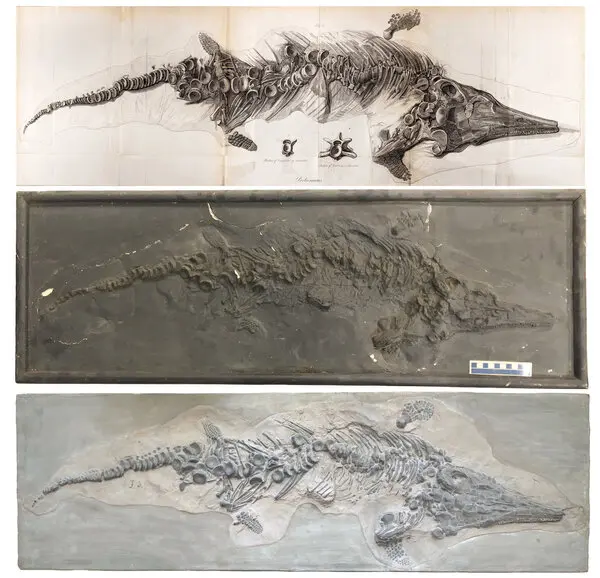

The fossil appeared eerily familiar to Lomax, a paleontologist at the University of Manchester who had never before visited the Peabody’s collection. It was remarkably identical to an old drawing of the earliest known Jurassic “sea dragon” skeleton, but it was not until he went through his photos afterwards that he made the connection. Three years later, in Germany, he discovered a cast that was comparable.

According to the latest news from Science, it turns out that both casts were created from the same object, which was the skeleton of an ichthyosaur, an ancient marine reptile with large eyes, a dolphin-like body, and an crocodile-like jaws that lived approximately 200 million years ago. The two casts are the only known representations of this species because the actual skeleton was destroyed during a bombing strike on London during World War II, according to Lomax’s current research.

The discoveries, according to experts, will enable researchers to study the historic ichthyosaur in unprecedented detail. Daniel Brinkman, a museum assistant in the Peabody’s vertebrate paleontology department who helped Lomax research the Yale cast, notes that paleontologists had only used a 200 year old image of the creature as their main source of information. He claims that the new casts provide a chance to assess how well historical depictions correspond to the actual specimens. “This report will have people taking a closer look at some of their casts.”

Ichthyosaurs were the leading lights of the developing field of paleontology decades before the word “dinosaur” made its way into the scientific language. The first complete ichthyosaur skeleton was discovered in Lyme Regis, on the famous Jurassic Coast in southern England. The residents of a tropical sea from 200 million years ago, including squid-like ammonites, pterosaurs, and a slew of marine reptiles, including ichthyosaurs and long-necked plesiosaurs, are eroding out of the region’s wave-battered limestone cliffs.

For generations, fossil hunters have come to these crumbling cliffs, in part because of the colossal collection of early 1800s pioneering scientist Mary Anning. By the time Anning was 12 years old, she and her brother had discovered a whole ichthyosaur skull. Anning is the daughter of an avid fossil digger. At the age of 18, she found the ichthyosaur specimen that was the most complete one at the time.

The amazing discovery gave early paleontologists a tantalizing peek of what these enigmatic prehistoric reptiles really looked like. “This specimen was a major piece of the gigantic prehistoric jigsaw puzzle,” Lomax said.

The fossil passed into the hands of a collector, who later sold it to help the Anning family through financial hardship. The skeleton eventually found its way into the collection of the Royal College of Surgeons in London, where British surgeon Sir Everard Home studied it. He incorrectly assumed that ichthyosaurs were a link between lizards and salamanders based on the creature’s flattened, disk-shaped vertebrae.

Anning discovered five ichthyosaur specimens, and Home published five papers on them, never mentioning Anning as the discoverer.

The London museum that housed the famous fossil was destroyed by a bomb from a German air raid in 1941. And for many years, it seemed that the scientific image that accompanied Home’s articles was the only trace of the first complete ichthyosaur specimen.

Then Lomax discovered the two casts, one of which was kept in the Berlin Natural History Museum’s storerooms.

Despite sharing the same source material, the two casts are not exact replicas of one another. The Berlin cast is in better condition and has been painted to mimic the 1819 depiction, whereas the older Yale specimen is more damaged and painted a consistent shade of ashen gray. According to Lomax and his co-author, paleontologist Judy Massare of the State University of New York, Brockport, the Yale cast seems to be a better portrayal of the original skeleton.

The Yale cast, in contrast to the Berlin cast, features a variety of characteristics—such as the quantity of intricate bones in the creature’s fore fins and the shape of the animal’s humerus—that set it apart from the other two portrayals. These minor characteristics, together with the plaster’s age and deterioration, make it likely that the Yale cast was one of the earliest ones created, possibly even before the skeleton was transported to London and described by Home. They transform from being merely another cast in the collection to serving as a representation of the first ichthyosaur skeleton to be described at the inception of paleontology, according to Lomax.

When researchers do not use casts to duplicate rare fossils, the outcomes might be disastrous. During an allied bombing of Munich in 1944, the earliest fossil evidence of the enormous carnivorous dinosaur Spinosaurus was destroyed, leaving only sketches and blurry images. Before new fossil evidence was discovered, the predator had remained little more than a sail-backed mystery for 50 years.

As museums shift to digitizing significant fossils, castings are now even simpler to make thanks to the development of 3D scanning technology.

Cover Photo: Example of the ichthyosaur skeleton found at Rutland Water Nature Reserve. (Matthew Power Photography)