Declassified photographs of the Middle East from Cold War spy satellites have revealed hundreds of previously unknown lost Roman forts in the deserts of Syria and Iraq. The discovery shows that the ancient frontier between the Romans and the east was a place of cultural exchange, not constant warfare.

The fortresses were scattered across the Syrian Steppe, now part of Syria and Iraq, to protect the eastern provinces from Arab and Persian raids.

According to researchers, the fortresses are located in an area where an aerial survey conducted by Father Antoine Poidebard in 1934 identified a defense line of 116 fortresses.

“Since the 1930s, historians and archaeologists have debated the strategic or political purpose of this system of fortifications,” says lead author Prof. Jesse Casana from Dartmouth College, “but few scholars have questioned Poidebard’s basic observation that there was a line of forts defining the eastern Roman frontier.”

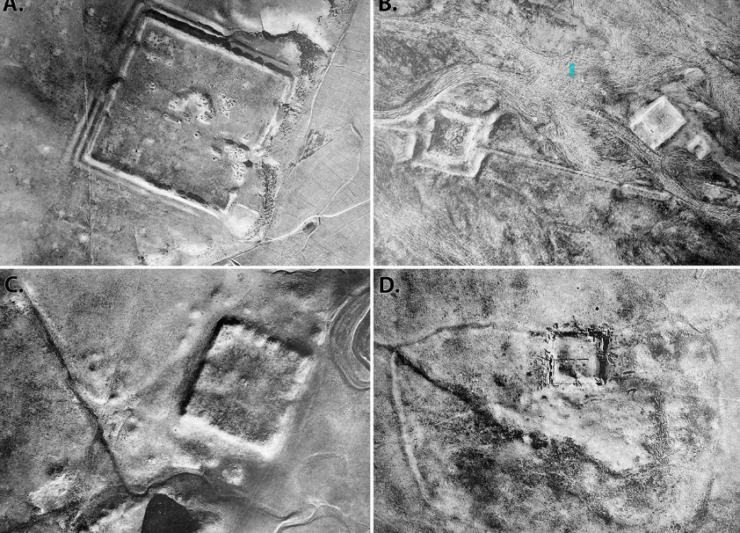

In the study, published in the journal Antiquity, a team from Dartmouth College examined declassified images of the first spy satellite program to determine whether Poidebard’s findings were accurate.

In a landscape substantially altered by contemporary changes in land-use, the study identified 396 new fort locations using the forts discovered by Poidebard as a point of reference. The forts were found throughout the region, stretching from east to west, contradicting the theory that they formed a north-south boundary wall.

The study contends that the forts were built by the Romans in order to facilitate connection between the eastern and western areas, protect caravans traveling between the eastern provinces and non-Roman lands, and encourage interregional trade.

Most importantly, this implies that the borders of the Roman World were broader than previously believed. The Roman boundary in the east was probably not always a scene of bloodshed.

Despite having a powerful military, the Romans also valued trade and connection with areas outside of their own borders. This discovery could therefore significantly reshape our understanding of life on the Roman frontier.

Prof. Jesse Casana of Dartmouth College: “We were only able to confidently identify extant archaeological remains at 38 of Poidebard’s 116 forts. In addition, many of the likely lost Roman forts we have documented in this study have already been destroyed by recent urban or agricultural development, and countless others are under extreme threat.”

This is a complex and environmentally sensitive region where nomadic tribes were integral to trade and cultural encounters. Some of the newly discovered sites have been set aside for future archaeological research, but others are located in active military zones that are inaccessible to researchers.

It should be noted that the Middle East has always been the envy of nations throughout history, so opportunities for archaeological excavation are limited due to political instability resulting from conflicts over regional dominance, or economic crises.